I wrote this article, "The Importance of Educating Girls and Women" for the website. It was supposed to be up a few weeks ago, but unfortunately the designer had a family emergency, and now it's the holidays. I'm hoping the site will be up in early January. I am keeping my fingers crossed. In the meantime, i thought I'd put it up in case anyone was interested in reading more about the subject.

The Importance of Educating Girls and Women

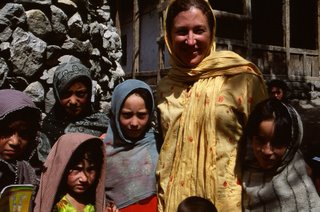

By Lizzy Scully

Until I traveled to Pakistan, India, and Bolivia I took my education for granted. With free access to everything I needed all the way through high school and a free ride through my first four years of college, thanks to my father, I never took education seriously. I did fairly well, but I didn’t appreciate the accessibility of good teachers, libraries, schoolbooks, computers, and all the other technological accoutrements common to my privileged world. The only time I really tried hard was in graduate school, where I earned a master’s in communication, and that’s only because I paid for everything myself.

Getting an education, even a college degree, is easy in the United States for both girls and boys. However, in many places around the world, women have little or no access to education. For example, less than one-third of Pakistani women are literate. In Nepal, women who can read make up just one-quarter of the population; and in India, only about half the women are literate. Countless studies show that uneducated women are more likely to suffer from poverty, illness, and malnutrition, and that their communities have high infant-mortality rates and lower productivity. According to a 1995 World Bank study, “Low levels of educational attainment and poor nutrition exacerbate poor living conditions and diminish an individual’s ability to work productively,” (World Bank, 1995b).

Because of this and countless other studies, the Western world has taken an increasing interest in educating women abroad. Laudable nonprofit and government-run organizations such as the Central Asia Institute, the Office of Women and Development/US Agency for International Development, and several others have focused on promoting literacy and integrated education (reading, writing, arithmetic) for women around the world. What they have discovered is not surprising, but has far-reaching consequences.

On a grand scale, research has illustrated that educating women and girls leads to an increased overall development and wellbeing both in communities and countries where females are educated. In Nepal, women who participated in integrated literacy programs were “more aware of health and reproductive health issues, political affairs, and the importance of children’s education,” (Bruchfield, Hua, Baral, Rocha, 2002).

Educated women are more likely to be aware of the importance of population control and taking their and their children’s health concerns more seriously. According to the organization Gender and Food Security, female education “significantly improve[s] household health and nutrition, lower[s] child morbidity and mortality rates, and slow[s] population growth.” And a 2005 United Nations study found that, “Education also helps to delay age at marriage and increase age at first child birth, thereby reducing the fertility rate. Awareness of the cost of children, increased knowledge of contraceptives, improved communication between couples, and sense of control over one’s life are also influenced by education, which in turn leads to smaller and healthier families,” (United Nations, 2005).

“Education is also associated with improved and timely access to information on good nutrition, good child-rearing practices, and earlier and more effective diagnosis of illnesses. As a result children born to educated mothers tend to be better nourished, fall sick less frequently, are healthier, and have a better growth rate than their uneducated counterparts,” (United Nations, 2005). Additionally, educated women have more awareness of problems such as HIV/AIDS.

Educated women are also more likely to stand up for themselves, understand their rights, participate in household decision-making, and to contribute to community or national politics. In 1997, the US Agency for International Development, working in Nepal, asserted that women who can read, write, and earn money “create more social change through organized and collective actions,” (Moulton, J. 1997). Women who have more control over money, whether it be through generating income on their own or by better understanding the needs of the family, tend to invest more in their children’s education and health and take care of their own health needs.

Furthermore, “women who have learned to read and understand their legal rights are much more likely to initiate action for social change than those who are illiterate … In the Dhanusha district in the Terai, women who completed literacy courses and had received ‘tin trunk libraries’ in their communities were keen to read women’s law books to know more about their rights in society,” (Bruchfield, Hua, Baral, Rocha, 2002).

Educated women also spend more time educating their own children, and the more education a woman has, the more likely she will be to send both her female and male children to school. According to one study, “The relationship between formal basic education and long-term economic growth is well documented, with numerous studies reporting a strong correlation between the education of girls and a country’s level of economic development (Bruchfield, Hua, Baral, Rocha, 2002).

Educational attainment also correlates to increased agricultural productivity. A recent report for the International Labour Organization stated that each additional year in school raised women’s earning by about 15%, compared with 11% for a man (Gender Food and Security).

Additionally, Gender and Food Security reported, “Increased education for women is not only a matter of justice, but would yield exceptional returns in terms of world food security. A World Bank study concluded that if women received the same amount of education as men, farm yields would rise by between seven and 22%. Increasing women’s primary schooling alone could increase agricultural output by 24%.”

Education for women could also be highly effective in the following areas: reducing the incidence of trafficking girls to brothels; increasing overall environmental awareness; and, reducing the likelihood of terrorism.

According to Greg Mortensen in his book, Three Cups of Tea, providing Pakistani and Afghani children with a well-rounded education typically makes them more moderate, and it provides them with an alternative to going to Madrassas—schools built and supported by Arab countries that promote a more radical, conservative form of Islam.

“The only way we can defeat terrorism is if people in this country where terrorists exist learn to respect and love Americans, and if we can respect and love these people here. What’s the difference between them becoming a productive local citizen or a terrorist? I think the key is education.” (Mortensen, Relin. 2006)

And as Mortensen stated in a March 2006 issue of the Roseville Review, “In Islam, when a young boy goes on jihad—it could be a good thing like getting a job or going to university, but it could be a bad thing like terrorism—he needs the permission and blessing from his mother.” If his mother was given a balanced education as a child, she is more likely to be moderate. Thus, while it takes time to bring change within the society, the costs are really low, and overall, “… it’s definitely worth the investment.”

References:

Bruchfield, S. Hua, H. Baral, D. Rocha, V. 2002. “A Longitudinal Study of the Effect of Integrated Literacy and Basic Education Programs on Women’s Participation in Social and Economic Development in Nepal,” December, 2002. Girls’ and Women’s Education Policy Research Activity website.

Fairbanks, G. 2006. “The Power of the Pen,” Roseville Review. Lillie Suburban Newspapers, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Gender and Food Security: Education, Extension, and Communication. file:///Users/elizabeth/Desktop/Gender%20and%20Food%20Security.webarchive.

Moulton, Jeanne. 1997. Formal and Nonformal Education and Empowered Behavior: A Review of Research Literature. Support for Analysis and Research in Africa (SARA) Project, US Agency for International Development.

United Nations, 2005. Commission on the Status of Women, fiftieth session. http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/csw/csw50/statements/CSW%2050%20-%20Panel%20I%20-%20Bernadette%20Lahai%20.pdf.

World Bank, 1995b. Toward Gender Equality: The Role of Public Policy. Washington, DC: World Bank.)

No comments:

Post a Comment